A new suicide prevention coalition has been impaneled, called together under the auspices of Lincoln Public Schools, although not an LPS committee per se. I was asked to serve, and readily agreed. The group of about 40 people convened for two hours last night at our first meeting, and I artfully avoided a leadership role by agreeing instead to assemble some data in advance of our second meeting.

I've blogged about suicide a few times before. I read all the suicide reports, and a fair share of the attempted suicides as well, particularly those reports that come in between midnight and 5:00 AM. I have access to lots of data, but I should really wait until the end of 2014 to do any serious work, so I'll be able to include the full year of 2014. Couldn't help myself, though. I was already digging in this morning.

Here's just a few tidbits of information. Over the past 20 years (sans the next two weeks) there have been 525 suicides in Lincoln, and 5,863 attempted suicides that came to the attention of the police. Of the completed suicides, 212 were with firearms, 40.4% of the total. The next most common method was hanging, followed by overdose and asphyxia. Cutting instruments and jumping from structures were 10 and 11, respectively.

After the first of the year, I'll be compiling some age and gender breakouts, creating some trend lines, and calculating some rates normalized by population. I will also be producing some maps, charts and graphs. Hopefully the members of the coalition will be better informed after looking at these products. I'll keep readers informed from time to time.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Wednesday, December 10, 2014

Liquor licenses proliferate

Officer Conan Schafer has recently taken over responsibility for overseeing liquor license investigation and enforcement at the Lincoln Police Department, and liaison with licensees and the City Council on such matters. He has been working on the police department's liquor license database, bringing everything up to date. I asked him to straighten up the addresses a little bit during this process, to try to get them into a consistent format so they will geocode more easily.

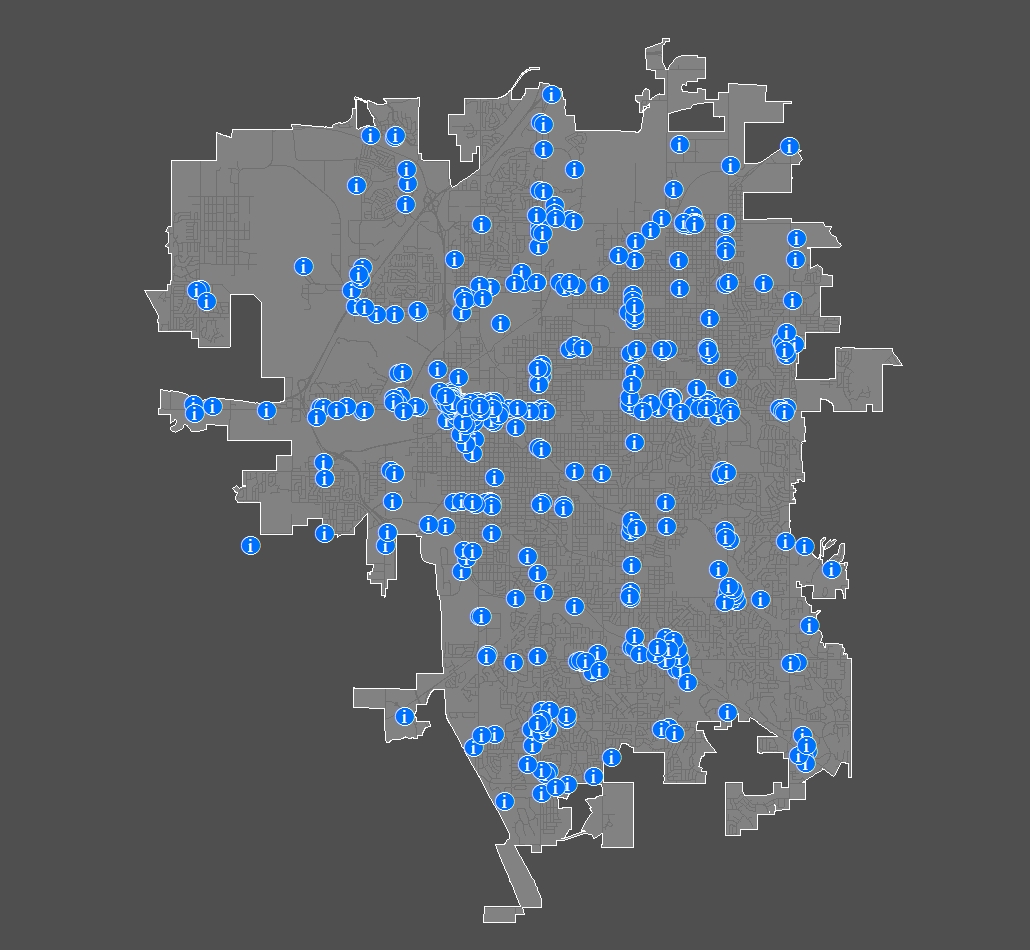

A few times a year, I need a geographic layer of liquor licenses for one reason or another--most recently to provide this information to HunchLab for their predictive algorithm. I usually have to spend some significant time cleaning up the addresses before geocoding, but this time it was a snap. Here's a map of the 481 liquor licenses in Lincoln right now:

I found a slide in a PowerPoint I did for a 2005 conference presentation, which pegged the number of liquor licenses at 373. We appear to have 108 more licenses in 2014 than in 2005, a 29% increase in the past decade. My vague recollection is that the entire City had less than 100 liquor licenses when I pinned on the badge in the summer of 1974.

There's a lot of research about the correlation of alcohol outlets with crime and disorder, particularly associating the density of outlets with these phenomenon. We certainly have some areas in Lincoln with a dense concentration of licenses, but I'm of the opinion that the relationship of alcohol outlets to crime and disorder is quite different based on the type of outlets and their business practices. Don't let the customers get drunk, and problems are considerably reduced, both inside the establishment and in the general neighborhood.

A few times a year, I need a geographic layer of liquor licenses for one reason or another--most recently to provide this information to HunchLab for their predictive algorithm. I usually have to spend some significant time cleaning up the addresses before geocoding, but this time it was a snap. Here's a map of the 481 liquor licenses in Lincoln right now:

|

| Click image for larger version |

I found a slide in a PowerPoint I did for a 2005 conference presentation, which pegged the number of liquor licenses at 373. We appear to have 108 more licenses in 2014 than in 2005, a 29% increase in the past decade. My vague recollection is that the entire City had less than 100 liquor licenses when I pinned on the badge in the summer of 1974.

There's a lot of research about the correlation of alcohol outlets with crime and disorder, particularly associating the density of outlets with these phenomenon. We certainly have some areas in Lincoln with a dense concentration of licenses, but I'm of the opinion that the relationship of alcohol outlets to crime and disorder is quite different based on the type of outlets and their business practices. Don't let the customers get drunk, and problems are considerably reduced, both inside the establishment and in the general neighborhood.

Friday, December 5, 2014

Vindicated

Last week, my lovely wife was hinting around about putting up some outdoor Christmas decorations. Our unadorned home is, well, standing out on the block somewhat. My position has been that those decorations you put up on a beautiful fall weekend, you'll have to take down on a bitter Saturday in January, so I have always resisted. Occasionally, especially when the kids were still at home, I would relent with a minimalist scheme intended to reduce my labor to the bare minimum needed in order to maintain domestic tranquility.

There is, however, another justification for my curmudgeonly refusal to participate in the garish commercialization of Christmas. Just as those pumpkins on the porch are nothing more than ammunition for vandals, those Christmas decorations are tempting targets for thieves. This morning in my inbox was this Crime Alert from crimemapping.com:

There you have it, boatloads of expensive décor swiped from lawns right in my own neighborhood. Yet another case-in-point I can pull out to explain to Tonja why I'm watching football tomorrow instead of stringing lights and inflating snowmen. I am vindicated.

Everyone in Lincoln should subscribe to Crime Alerts from crimemapping.com. For that matter, everyone in any jurisdiction that provides its data to the Omega Group for crimemapping.com should do so. Here in Nebraska, that's Lincoln Police, Omaha Police, Lancaster County Sheriff, and Grand Island Police. I'm signed up for my daughter's address in Omaha, my son's in Lincoln, and my own. It's free, easy and lets me know in a day when a crime I'm interested in has been reported nearby.

There is, however, another justification for my curmudgeonly refusal to participate in the garish commercialization of Christmas. Just as those pumpkins on the porch are nothing more than ammunition for vandals, those Christmas decorations are tempting targets for thieves. This morning in my inbox was this Crime Alert from crimemapping.com:

There you have it, boatloads of expensive décor swiped from lawns right in my own neighborhood. Yet another case-in-point I can pull out to explain to Tonja why I'm watching football tomorrow instead of stringing lights and inflating snowmen. I am vindicated.

Everyone in Lincoln should subscribe to Crime Alerts from crimemapping.com. For that matter, everyone in any jurisdiction that provides its data to the Omega Group for crimemapping.com should do so. Here in Nebraska, that's Lincoln Police, Omaha Police, Lancaster County Sheriff, and Grand Island Police. I'm signed up for my daughter's address in Omaha, my son's in Lincoln, and my own. It's free, easy and lets me know in a day when a crime I'm interested in has been reported nearby.

Tuesday, December 2, 2014

More not necessarily better

Back in 1994 when I was first appointed police chief in Lincoln, one of my priorities was to rewrite the department's policy manual, composed of a few hundred General Orders, covering everything from traffic direction to death notifications. The loose-leaf manual issued to every employee was bulging, bloated, and hopelessly inconsistent in style, individual General Orders having been authored by dozens of people over a couple decades, often in stilted, legalistic prose that sometimes seems to infect police work like a bad virus.

In 1995, I finally set to the task, and we rewrote the entire set. The result was a vastly more concise manual, slimmed down to about an inch. For the next 16 years, my operating rule was simple: if a new word went in, another word had to come out elsewhere. I did not want the manual to return to its former corpulence, because I have a strong belief that familiarity and compliance with a policy manual is inversely correlated with its length. It simply isn't reasonable to expect employees to ingest and remember a collection of policies that resembles the unabridged dictionary.

In the past few years, however, both the Lincoln Police Department and Lincoln Fire &Rescue have converted entirely to online policy manuals. While in most ways this is a good thing, one of the unintended side effects is that the swelling is less noticeable. The imperative to keep the manual svelte has to some extent evaporated. No one is sweating over every paragraph quite so much, trying to figure out how more succinct language could prevent page two from spilling over to a third page.

I acquired a great example of the problem several years ago, from another midwest capital city police department that shall remain nameless. It was a seven-page policy entitled "Escape of Zoo Animals." The seven pages included drawings showing the best shot placement, should it become necessary to deal with various large mammals. I can just imagine a police officer, confronted with a rampaging rhinoceros, reaching for the manual and thumbing to page 543 for instruction.

Of course, with an online manual you could just pull over to the curb and enter rhinoceros in the search box--that is, if you can spell rhinoceros. Some discipline will be necessary to keep the policies trim, and ensure that our employees really can be familiar with the most important guidelines they need to know, and to find the relevant content easily when in doubt.

In 1995, I finally set to the task, and we rewrote the entire set. The result was a vastly more concise manual, slimmed down to about an inch. For the next 16 years, my operating rule was simple: if a new word went in, another word had to come out elsewhere. I did not want the manual to return to its former corpulence, because I have a strong belief that familiarity and compliance with a policy manual is inversely correlated with its length. It simply isn't reasonable to expect employees to ingest and remember a collection of policies that resembles the unabridged dictionary.

In the past few years, however, both the Lincoln Police Department and Lincoln Fire &Rescue have converted entirely to online policy manuals. While in most ways this is a good thing, one of the unintended side effects is that the swelling is less noticeable. The imperative to keep the manual svelte has to some extent evaporated. No one is sweating over every paragraph quite so much, trying to figure out how more succinct language could prevent page two from spilling over to a third page.

I acquired a great example of the problem several years ago, from another midwest capital city police department that shall remain nameless. It was a seven-page policy entitled "Escape of Zoo Animals." The seven pages included drawings showing the best shot placement, should it become necessary to deal with various large mammals. I can just imagine a police officer, confronted with a rampaging rhinoceros, reaching for the manual and thumbing to page 543 for instruction.

Of course, with an online manual you could just pull over to the curb and enter rhinoceros in the search box--that is, if you can spell rhinoceros. Some discipline will be necessary to keep the policies trim, and ensure that our employees really can be familiar with the most important guidelines they need to know, and to find the relevant content easily when in doubt.

Friday, November 21, 2014

Geocoding crucial

The Director's Desk readership includes a lot of analysts and GIS aficionados. I'm going to geek out in this post, so unless you are among them, consider yourself forewarned.

Public safety analysts and technicians mine data from dispatch records, incident report, and other databases in order to work with these data in a GIS framework. The dots don't appear on the maps magically, though. The geocoding process uses software algorithms to convert the text description of an address into a point on a map.

Geocoding is both art and science, and accuracy is important. If large numbers of events will not geocode, or geocode improperly, the validity of any analysis is compromised. It doesn't take much to throw things off, either, because geocoding errors are often not random. Rather, they tend to be systematic: the same address gets missed over and over, or a tiny error in a street reference file results in the same address getting incorrectly placed on the wrong side of a census tract boundary, evey single time.

Because of this, accuracy of geocoding should be a top concern for those of us who manage GIS applications. The key is to understand what isn't geocoding properly, and to systematically correct as much of that is possible. You may not be able to prevent the occasional fat-fingered entry where someone inserted an extra zero in an address field, but if you can never properly geocode the street address of a local high school, you've got to figure out why and correct that.

Here in Lincoln, we're geocoding a few hundred thousand police and fire incidents and dispatches annually. I watch the unmatched records closely, in order to monitor any consistent geocoding problems. So I was pretty pleased to see this geocoding history report for recent fire dispatches yesterday morning:

Hard to top that, in almost a thousand records that are updated twice daily. That's the Omega Group's Import Wizard software pictured in this screen shot, which manages the data import and geocoding from both police and fire records systems in Lincoln, in order to populate CrimeView and FireView applications.

My advice to analysts is not to be complacent even if you have a high hit rate. Keep an eye on your unmatched records, find the repeats, figure out why, and fix the problem whenever possible.

Public safety analysts and technicians mine data from dispatch records, incident report, and other databases in order to work with these data in a GIS framework. The dots don't appear on the maps magically, though. The geocoding process uses software algorithms to convert the text description of an address into a point on a map.

Geocoding is both art and science, and accuracy is important. If large numbers of events will not geocode, or geocode improperly, the validity of any analysis is compromised. It doesn't take much to throw things off, either, because geocoding errors are often not random. Rather, they tend to be systematic: the same address gets missed over and over, or a tiny error in a street reference file results in the same address getting incorrectly placed on the wrong side of a census tract boundary, evey single time.

Because of this, accuracy of geocoding should be a top concern for those of us who manage GIS applications. The key is to understand what isn't geocoding properly, and to systematically correct as much of that is possible. You may not be able to prevent the occasional fat-fingered entry where someone inserted an extra zero in an address field, but if you can never properly geocode the street address of a local high school, you've got to figure out why and correct that.

Here in Lincoln, we're geocoding a few hundred thousand police and fire incidents and dispatches annually. I watch the unmatched records closely, in order to monitor any consistent geocoding problems. So I was pretty pleased to see this geocoding history report for recent fire dispatches yesterday morning:

Hard to top that, in almost a thousand records that are updated twice daily. That's the Omega Group's Import Wizard software pictured in this screen shot, which manages the data import and geocoding from both police and fire records systems in Lincoln, in order to populate CrimeView and FireView applications.

My advice to analysts is not to be complacent even if you have a high hit rate. Keep an eye on your unmatched records, find the repeats, figure out why, and fix the problem whenever possible.

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Foiled by Facebook

An interesting case (B4-106047) early this morning caught my attention in today's police reports. Shortly after midnight, an officer was dispatched to a downtown bar, after an employee became suspicious of a customer's true identity. It seems the employee checked her ID to determine if she was of legal age, but noticed that the name on the ID and the name on the credit card presented for payment did not match.

The police were summoned. The customer told the investigating officer that the ID was hers, but the credit card was her mother's, which she had permission to use. The photo ID looked like her, but the officer wasn't completely certain. Lacking any evidence to the contrary, however, no further action was taken. Afterwards, the employees did a little research of there own, and found the social media profile of the name on the credit card. Sure enough, it was unmistakably the customer, who had apparently "borrowed" an ID from someone that looked similar enough to her that it wasn't obvious to the officer at the scene.

The customer had slipped out, so the bar employee notified the officer, and showed her what they had found. She then contacted the defendant by cellphone. She fessed up to the scheme, and voluntarily agreed to meet the investigating officer at police headquarters to receive her citations for minor attempt to purchase alcohol and providing false information to a police officer.

You can find most anything on the Internet these days. Nice work, Duffy's!

The police were summoned. The customer told the investigating officer that the ID was hers, but the credit card was her mother's, which she had permission to use. The photo ID looked like her, but the officer wasn't completely certain. Lacking any evidence to the contrary, however, no further action was taken. Afterwards, the employees did a little research of there own, and found the social media profile of the name on the credit card. Sure enough, it was unmistakably the customer, who had apparently "borrowed" an ID from someone that looked similar enough to her that it wasn't obvious to the officer at the scene.

The customer had slipped out, so the bar employee notified the officer, and showed her what they had found. She then contacted the defendant by cellphone. She fessed up to the scheme, and voluntarily agreed to meet the investigating officer at police headquarters to receive her citations for minor attempt to purchase alcohol and providing false information to a police officer.

You can find most anything on the Internet these days. Nice work, Duffy's!

Monday, November 17, 2014

Learning curve

The blast of winter weather last week caught motorists in Lincoln off guard. Balmy temperatures in the 60s during the first week of November were followed by single digits last week, with a couple dustings of snow. It seems that every year there is a certain learning curve, as motorists try to adapt to winter driving conditions.

Tuesday morning's commute was light, due to the fact that government offices and financial institutions were closed for Veteran's Day, but Lincoln drivers managed to get involved in 84 traffic crashes nonetheless. It was not even measurable precipitation, but just enough to glaze the streets. On Saturday, a whopping 1.5 inches of snowfall resulted in 81 crashes: almost four times the daily average.

I noted an interesting pattern to the collisions when I did an hour-of-the-day analysis using CrimeView Dashboard. The first graph shows the distribution by time of day for crashes on Tuesday, November 11. The second graph is for Saturday, November 15.

As you can see, Tuesday's crashes spiked in a two-hour window during the morning drive-time, after which street conditions quickly improved. Saturday's crashes were spread more throughout the day. Notice the dip on Saturday at 1400 hours, when most Nebraskans were finding a TV in order to watch a football game that turned out to be something of a let down.

Time to refresh the basics: leave earlier, take your time, go easy on the gas when accelerating, keep a healthy following distance, anticipate your stops, and make sure you can see the spot where the tires of the vehicle ahead touch the pavement when you come to a stop in traffic. If you've been thinking the tread is getting a little worn, it would be a good time now to replace those tires and improve your grip.

Tuesday morning's commute was light, due to the fact that government offices and financial institutions were closed for Veteran's Day, but Lincoln drivers managed to get involved in 84 traffic crashes nonetheless. It was not even measurable precipitation, but just enough to glaze the streets. On Saturday, a whopping 1.5 inches of snowfall resulted in 81 crashes: almost four times the daily average.

I noted an interesting pattern to the collisions when I did an hour-of-the-day analysis using CrimeView Dashboard. The first graph shows the distribution by time of day for crashes on Tuesday, November 11. The second graph is for Saturday, November 15.

As you can see, Tuesday's crashes spiked in a two-hour window during the morning drive-time, after which street conditions quickly improved. Saturday's crashes were spread more throughout the day. Notice the dip on Saturday at 1400 hours, when most Nebraskans were finding a TV in order to watch a football game that turned out to be something of a let down.

Time to refresh the basics: leave earlier, take your time, go easy on the gas when accelerating, keep a healthy following distance, anticipate your stops, and make sure you can see the spot where the tires of the vehicle ahead touch the pavement when you come to a stop in traffic. If you've been thinking the tread is getting a little worn, it would be a good time now to replace those tires and improve your grip.

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

Flyover country

Nebraska's are all familiar with the fact that millions of Americans living in big cities and on the coasts are geographically challenged. It happens like this: you encounter someone from Massachusetts in the airport lounge in Atlanta, and strike up a conversation. "Where are you from?" she asks. "Nebraska," you respond. "Oh," she says, "I love Las Vegas!"

There are, however, major advantages to living in flyover country, among which is that you generally can figure out east, west, north, and south--even up and down--quite a bit better than your fellow citizens in more populous places. Smug in the knowledge that Lincoln is actually the 72nd largest city in the USA, I simply smile at the misconceptions harbored by those who navigate by subway stops and freeway numbers.

So, I'm sitting in the living room yesterday morning, reading the news on my MacBook and encounter a bunch of links to news stories about the FBI's annual release of their statistical report, Crime in America. One of the links is to an online database at the Detroit Free Press. I'm always interested in these journalistic data projects, so I followed the link, and went to look up Lincoln--just to ensure the data was accurate.

Low and behold, Nebraska appears to have left the Union!

There are, however, major advantages to living in flyover country, among which is that you generally can figure out east, west, north, and south--even up and down--quite a bit better than your fellow citizens in more populous places. Smug in the knowledge that Lincoln is actually the 72nd largest city in the USA, I simply smile at the misconceptions harbored by those who navigate by subway stops and freeway numbers.

So, I'm sitting in the living room yesterday morning, reading the news on my MacBook and encounter a bunch of links to news stories about the FBI's annual release of their statistical report, Crime in America. One of the links is to an online database at the Detroit Free Press. I'm always interested in these journalistic data projects, so I followed the link, and went to look up Lincoln--just to ensure the data was accurate.

Low and behold, Nebraska appears to have left the Union!

Monday, November 10, 2014

The F word

Dr. Samuel Walker, one of the most well-known experts on civil liberties and criminal justice in the United States, taught at the University of Nebraska at Omaha for over 30 years. His tenure overlapped my college career, and although I am a graduate of his department, I never had him as a professor. I don't always agree with Dr. Walker's positions, but last week he published a short paper which is spot-on.

It concerns the F word, and more broadly profanity and disrespectful language in general. This has no place in police interactions with the public, and I agree completely with Dr. Walker that it should be eliminated from the vocabulary. Profanity in public interactions is prohibited by policy, and I've dealt with several officers and deputies over this as a supervisor. Nonetheless, I'm not sure it has completely sunken in to everyone how corrosive it is to respect for the police.

We live in a culture where F-bombs are not uncommon, even in otherwise polite conversation. When it comes from a police officer, however, it has an entirely different connotation. I'm not naïve, and I'm not unfamiliar the salty language one hears in a squad room, and pretty tolerant thereof--so long as it is not racist, sexist, or homophobic--but this is way different than slinging profanity on the street and to the public.

All police officers need to practice self-control, even when confronted with people who are spewing the most hateful and vile language imaginable in their face.

It concerns the F word, and more broadly profanity and disrespectful language in general. This has no place in police interactions with the public, and I agree completely with Dr. Walker that it should be eliminated from the vocabulary. Profanity in public interactions is prohibited by policy, and I've dealt with several officers and deputies over this as a supervisor. Nonetheless, I'm not sure it has completely sunken in to everyone how corrosive it is to respect for the police.

We live in a culture where F-bombs are not uncommon, even in otherwise polite conversation. When it comes from a police officer, however, it has an entirely different connotation. I'm not naïve, and I'm not unfamiliar the salty language one hears in a squad room, and pretty tolerant thereof--so long as it is not racist, sexist, or homophobic--but this is way different than slinging profanity on the street and to the public.

All police officers need to practice self-control, even when confronted with people who are spewing the most hateful and vile language imaginable in their face.

Friday, October 31, 2014

Hidden cost of body-worn cameras

There is a growing movement afoot in the United States to put cameras on police officers. It is gathering momentum, perhaps as a result of the shooting of Michael Brown by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri this past summer. The movement involves some strange bedfellows: both police supporters, and some groups that are, well, not exactly known as best buds of the police. Here locally, the ACLU has been advocating body worn cameras for Lincoln police officers lately.

I like body worn video. I handled a particular model several years ago at a conference, and thought it was the first really practical and affordable one I had seen. I came back to Lincoln, and we acquired four of those. They worked well, and didn't break the bank. I'd love to have even more, but I don't think we are anywhere close to ready, despite the clamor.

This reminds me of a similar effort to get cameras into police cars in the mid 1990's. The technology of the time, usually a consumer-grade camera recording to 8mm tape, was really not up to the task, and many departments plunged headlong into video systems only to find that they had inadvertently created their own nightmare. They didn't plan for such things as the cost and logistics of storing and retrieving video, training, tagging evidentiary clips, installing, maintaining, and replacing equipment.

By the end of the decade, you could commonly read news stories about departments where half of the cameras were out of service at any given time, or the department was scrambling to find money to replace broken and outdated equipment. The problem abated as some departments scaled back their installations to a manageable number, and as the technology improved. Today, digital in-car camera systems are a much more mature technology, and though expensive, we've learned the lessons of the 1990s on how to make such a program work. I'm glad in hindsight, that we didn't dive into the water too early in Lincoln, and waited until the technology improved.

I worry that the same thing is happening with body-worn video. In some ways, it is a disruptive technology: a game-changer that leap frogs vehicle-mounted systems. If I were a street officer today, I would want one badly, to both help me collect iron-clad evidence, and protect me from bogus complaints. But departments who head down this road better be cautious not to repeat the errors of the past.

The reason I think this is such a risk is that the cost of the cameras themselves is fairly modest (around $800 to $1200 for a camera and the accessories). That's a lot of money for a big department but still, seems quite doable if you put your mind to it. As a result, equipping cops with cameras looks pretty attractive. But there are much larger hidden costs, along with logistical and policy issues, and I'm not sure people have thought through these completely, and are fully prepared to deal with them.

Fortunately, the Department of Justice and the Police Executive Research Forum have both recently released very good reports on the myriad of considerations surrounding body worn cameras. These reports would be valuable reading for camera advocates and for police chiefs.

Just dealing with the financials, I did a little math on what it would cost to equip about 240 Lincoln police officers, sergeants, and detectives with body-worn video. I used the data from the two reports, which came primarily from New Orleans, LA and Mesa, AZ. The start up cost doesn't look too bad:

240 cameras and accessories x $1,000 = $240,000

Okay, that's a lot, but surely we could figure out a way. But there's more--the cost of operations that you'll experience every year:

One technician to support the systems and manage the data $65,000

Annual cost of data storage and management $240,000

Replacement of one third of cameras each year $80,000

Total annual cost $385,000

I think these estimates may even be a bit low. There is another hidden cost, though, in the time each user would need to devote to reviewing video, tagging and uploading video to a server or cloud service. If you figure that at ten minutes per shift, which would be very conservative, your looking at something north of 6,000 person hours per year--the equivalent of three full time police officers.

My guess is that there will ultimately be an evolution of this technology, so that storage costs fall, automatic uploading and tagging improves, and software tools get better, requiring less personnel time. Hardware will get better, with such things as longer battery life and lower pricing, and less expensive back-end storage-retreival-management solutions. Body worn camera systems will be more practical, and will become more widespread.

I like body worn video. I handled a particular model several years ago at a conference, and thought it was the first really practical and affordable one I had seen. I came back to Lincoln, and we acquired four of those. They worked well, and didn't break the bank. I'd love to have even more, but I don't think we are anywhere close to ready, despite the clamor.

This reminds me of a similar effort to get cameras into police cars in the mid 1990's. The technology of the time, usually a consumer-grade camera recording to 8mm tape, was really not up to the task, and many departments plunged headlong into video systems only to find that they had inadvertently created their own nightmare. They didn't plan for such things as the cost and logistics of storing and retrieving video, training, tagging evidentiary clips, installing, maintaining, and replacing equipment.

By the end of the decade, you could commonly read news stories about departments where half of the cameras were out of service at any given time, or the department was scrambling to find money to replace broken and outdated equipment. The problem abated as some departments scaled back their installations to a manageable number, and as the technology improved. Today, digital in-car camera systems are a much more mature technology, and though expensive, we've learned the lessons of the 1990s on how to make such a program work. I'm glad in hindsight, that we didn't dive into the water too early in Lincoln, and waited until the technology improved.

I worry that the same thing is happening with body-worn video. In some ways, it is a disruptive technology: a game-changer that leap frogs vehicle-mounted systems. If I were a street officer today, I would want one badly, to both help me collect iron-clad evidence, and protect me from bogus complaints. But departments who head down this road better be cautious not to repeat the errors of the past.

The reason I think this is such a risk is that the cost of the cameras themselves is fairly modest (around $800 to $1200 for a camera and the accessories). That's a lot of money for a big department but still, seems quite doable if you put your mind to it. As a result, equipping cops with cameras looks pretty attractive. But there are much larger hidden costs, along with logistical and policy issues, and I'm not sure people have thought through these completely, and are fully prepared to deal with them.

Fortunately, the Department of Justice and the Police Executive Research Forum have both recently released very good reports on the myriad of considerations surrounding body worn cameras. These reports would be valuable reading for camera advocates and for police chiefs.

Just dealing with the financials, I did a little math on what it would cost to equip about 240 Lincoln police officers, sergeants, and detectives with body-worn video. I used the data from the two reports, which came primarily from New Orleans, LA and Mesa, AZ. The start up cost doesn't look too bad:

240 cameras and accessories x $1,000 = $240,000

Okay, that's a lot, but surely we could figure out a way. But there's more--the cost of operations that you'll experience every year:

One technician to support the systems and manage the data $65,000

Annual cost of data storage and management $240,000

Replacement of one third of cameras each year $80,000

Total annual cost $385,000

I think these estimates may even be a bit low. There is another hidden cost, though, in the time each user would need to devote to reviewing video, tagging and uploading video to a server or cloud service. If you figure that at ten minutes per shift, which would be very conservative, your looking at something north of 6,000 person hours per year--the equivalent of three full time police officers.

My guess is that there will ultimately be an evolution of this technology, so that storage costs fall, automatic uploading and tagging improves, and software tools get better, requiring less personnel time. Hardware will get better, with such things as longer battery life and lower pricing, and less expensive back-end storage-retreival-management solutions. Body worn camera systems will be more practical, and will become more widespread.

Monday, October 27, 2014

Public safety project FAQs

We're getting lots of questions and comments in response to the City's online survey about budget issues, "Taking Charge." Two pending public safety projects are highlighted in the survey, the replacement of our aging radio system, and the plan to relocate four fire stations, one of which would be a joint police/fire facility. I've been watching the survey feedback, and some issues are coming up repeatedly. I hit on one of these at length last Friday, but I've put together some Frequently Asked Questions.

Why hasn’t the City been saving the funds needed to replace the radio system?

While it would certainly have been possible to budget funds annually over a period of years in order to accumulate enough money for a radio system, this is seldom how large capital outlay projects are financed. To make an analogy, few people save for years in order to pay cash for a home, or for that matter even a new car. Past radio systems have been funded with general obligation bonds, like other major municipal infrastructure. Even if the city had attempted to save up $20.5 million to pay cash for a radio system, the tight budget since 2000 would have made it incredibly difficult to do so without major cuts to the services funded in the City’s annual operating budgets.

Why does there seem to be a lack of specifics about the radio system?

Public safety radio systems for jurisdictions of our size are complex, and not easily described in a few sentences. Detailed information, however, is available in our consultant’s full 81 page report, available online at: http://is.gd/radiosystemstudy. The consultant’s report, though, is not a proposal from an actual radio system vendor. After the City releases a Request for Proposals, each prospective vendor will need to develop their own plan to meet the City’s requirements. Different vendors are likely to have different approaches. Many of the specifics about exact system design and engineering and precise costs will have to await detailed proposals from the bidders.

Why is the radio system so expensive?

Public safety radio systems are engineered for reliability and redundancy. Towers and shelters are constructed to high standards, and sites include backup generators and power supplies. The radios carried by public safety staff and installed in police cars and fire apparatus are built to withstand the harsh use of law enforcement officers and fire and rescue personnel. The radio system directly impacts the safety of the public, as well as the safety and efficiency of our public safety professionals. Reliability, robustness, and resilience are necessary to assure that the radio system functions properly in critical circumstances. While a public safety radio system is certainly a major expense, to put it in perspective it will cost about the same as the replacement of the Harris Overpass a few years ago, and significantly less than a new elementary school.

How long will a new radio system last?

Radio systems need regular maintenance, software and hardware updates. A significant upgrade is likely to be needed about every 8-10 years, just like our current radio system. These costs are in our annual operating budget now, and we have done two significant upgrades during this system’s 27 year life. Some components need to be replaced regularly, such as computers and software, and some will last for decades with proper care, such as towers and shelters. With ongoing maintenance and updates, the radio system lasts as long as the technology is supported by the manufacturer. Our current system, EDACS, was launched in 1987, and vendor support ends in 2017. With the increasing pace of technological change our next system’s underlying technology may not last 30 years like the current system, but 20 would not be an unreasonable estimate.

Can’t the public safety agencies just use cellphones for communications?

Ever dropped a cell phone, or got one all really wet? More importantly, cellular telephone systems are not engineered for the same level of reliability as a public safety radio system. Cell service is typically lost in events such as hurricanes, tornadoes, or ice storms. In emergency circumstances, even if cell sites are not compromised, the capacity of these systems is often exceeded as thousands of customers attempt to use their cell phones at the same time. Basically, when you most need to communicate on a cellular telephone network, it is least likely to actually work. Public safety radio systems are engineered to withstand the environments in which they are utilized. In addition, they are designed with redundancies to protect against a single point of failure, and to ensure public safety personnel do not lose communications in a disaster or during a critical event.

Could our public safety agencies just use the State radio system?

The Nebraska Statewide Radio System does not have sufficient capacity in Lincoln and Lancaster County to handle the load of nearly 2,500 additional radios that presently on the City of Lincoln system. Moreover, it operates in the VHF frequency band, optimized for outdoor mobile (vehicular) coverage in a rural setting. The City’s system, on the other hand, operates in the 800 MHz band, which is superior for building penetration, and is optimized for indoor portable (hand-held) coverage in an urban setting. Nonetheless, we could build (at our own expense) infrastructure needed for coverage in Lincoln and Lancaster County, add that to the Statewide Radio System assets, and share some of the network components, particularly the switches and computers that control the system. This is an option that we are considering, and we expect to see one or more vendor propose such an arrangement in response to our Request for Proposals. At this point, we cannot say that joining the state system will be either the best or the least expensive solution.

Will the other users pay their share?

About one-third of the users of our radio system are not City of Lincoln agencies. Over the years, Lincoln invited State, County, and other users to operate radios on our system. We did so because it was advantageous for us to have nearby public safety agencies like the University of Nebraska Police Department, Lancaster County Sheriff, Capital Security Division of the State Patrol, and Airport Authority Police on the same network. Our police and fire personnel interact daily with these agencies. We also invited these users in order to spread the annual cost of operations across a larger user group. Each user pays an annual per-radio fee that offsets the total cost of operations. What these non-City users did not pay for was the central network and system itself. In a sense, as we had to build it anyway, revenue from non-City users was a good deal for Lincoln. With a new radio system, we will continue to charge an annual fee to non-City users, and we intend to recoup at least a portion of the system/network acquisition costs.

Why do fire engines respond to medical emergencies, instead of just an ambulance?

Ambulances carry two personnel. For most medical emergencies, more are needed for patient care. Consider someone experiencing chest pain, for example. First responders need to assess the patient, start an IV, administer drugs, connect an EKG, maintain an airway, communicate with the emergency room staff, monitor vital signs, and perform several other tasks. This really requires a team. Think of the size of the team that will attend this patient once he or she arrives at the hospital. In addition, just moving a patient often requires more than two personnel. Back injuries are the leading source of firefighter injuries in Lincoln, and patients are not getting smaller. The team arrives in two vehicles. The crew from the fire station is usually closer, because there are more fire apparatus than ambulances, and because the ambulances are more likely to be handling another call. All of our firefighters are emergency medical technicians, and many of our fire apparatus are also staffed with at least one paramedic. They also carry defibrillators and medical equipment. Thus, the fire crew is the quickest way to get a trained EMS provider at the patient’s side. They travel on a fire engine or truck simply because that is the vehicle they have. We have been testing an alternate response vehicle lately, essentially a crew cab pickup loaded with supplies, and a smaller vehicle may be a growing trend for responses to most medical emergencies as an alternative to the fire apparatus.

What is so important about four minutes travel time from a fire station?

Four minutes travel time to life-threatening emergencies is a national standard for urban fire and rescue services, adopted by the National Fire Protection Association and widely used as the benchmark U.S. cities. It is important, because the amount of time from the onset of an emergency to the arrival by emergency equipment and personnel makes a big difference in the outcome. A few minutes delay in the event of a stroke, fire, traumatic injury, cardiac or respiratory arrest can literally be the difference between life and death.

How far beyond the four minute travel time standard are houses and businesses in Lincoln?

There were 9,783 addresses in Lincoln beyond four minutes from a fire station as of August 25, 2014, 11% of the total addresses in Lincoln. The number goes up a little bit every week, as new building permits are issued and as construction occurs. Of those, 3,246 were more than five minutes from a fire station, and 613 are more than six minutes from a fire station. This is changing quickly, though, as considerable development occurs in northeast, southeast, and south Lincoln in the areas that are furthest from existing fire stations. Even more development in these areas is anticipated in the City’s Comprehensive Plan.

What would happen to the two fire stations that would be closed?

These facilities could be declared surplus, sold, and returned to the tax rolls. Alternatively, they could be repurposed for some other public use. For the first 100 years of Lincoln Fire & Rescue’s history, we occasionally moved fire stations to new locations to deal with the expanding city. Five of these former fire station buildings survive today. Former fire stations have become such things as a community center, Greek house, consignment shop, restaurant, art center, appliance store, and a recreation center.

Why don’t we just add four more staffed fire stations, rather than moving two stations and relocating existing equipment and personnel to two other newly-constructed stations?

By far the biggest cost of adding fire stations is staffing. It takes about 14 firefighters to staff a single apparatus at a fire station around the clock. The annual personnel costs would exceed a million dollars for each station. Unlike the construction cost, the payroll is an ongoing expense every year. As we dig out from the largest economic recession since the Great Depression, the City budget simply cannot take on this added expense without massive cuts to other City services or large tax increases.

What will the new fire stations look like?

We hired an architectural firm to produce a design. The new stations will look pretty much like newer fire stations around the country: utilitarian buildings with the basic areas needed for daily operations. These don’t vary much from city to city: a dormitory area, lockers and restrooms, an office, a day room and kitchen. The dominant feature of a fire station is the apparatus floor: the garage where the apparatus and equipment are kept. We hope to avoid two mistakes made on some of our older stations, insufficient apparatus space, and inadequate facilities to accommodate both male and female staff. One of the stations in Southeast Lincoln would be a joint police and fire facility, where about 50 police personnel would report for duty during the week. This would be significantly larger, with the same type of space found in Lincoln’s other two police substations at 27th and Holdrege and 49th and Huntington. Police officers who work in southeast Lincoln presently deploy from downtown. Response times and coverage are problematic due to the long distance these officers must travel at shift change. Significant fuel savings and personnel savings would also be realized with a southeast police station. With a joint facility, architectural fees, land acquisition costs, and some of the basic construction costs will be lower compared to separate police and fire stations. In addition, some of the interior spaces can be shared, lowering the total square footage needed in comparison to separate stations.

Friday, October 24, 2014

Why not use cellphones?

I've been asked this question several times lately, as I make the speaking circuit and talk about the need to replace the City's aging radio system. It's a perfectly understandable question, as everyone these days is tethered to their smartphone. To be sure, cell phones are a terrific convenience. They are used all the time by public safety staff, but not for critical communications. There's good reason for that

Police officers and firefighters, are not having one-to-one conversations over the radio system. Rather, their radio traffic is one-to-many. It's a fundamental difference between a cell phone call and a public safety broadcast. Technically, you could use the same cell phone infrastructure to carry a group call, but the more serious limitations of cell phones for emergency communications lie in the design and engineering of the equipment and systems.

Ever drop your smartphone? If so, you had that sinking feeling, because we all know that the chances of it working when you pick it up are iffy. Cracked screens are a dime a dozen. How long do you think a smartphone would hold up in a foot pursuit? Do you think it would work if it got really, really wet, like directing traffic in a downpour, or on the fireground? Sure, you could encase it in the Binford 5000 case (is that reference beginning to date me?), but are you willing to bet your life on that? Public safety radios are weather-sealed, robust and mil-spec. The even greater concern, however, is not the end-user device, but rather the system itself.

Cell sites are not built to the same standard as public safety radio sites, which are engineered to withstand higher stress from such things as wind, lightning strikes, ice, and natural disasters. Public safety radio systems are designed with backups and redundancies to minimize the likelihood of failure. They also manage traffic differently, giving users priority for access to the system based on the criticality of their function. If you've ever tried using your cellphone at a big event, like a football game, festival, or mass gathering, you've probably experienced difficulty getting access to make a call. Traffic can overwhelm cell sites pretty quickly, as hundreds or thousands of users are competing for the same resources at the same time in the same area.

Experience around the country in critical incidents and events, like hurricanes, tornadoes, windstorms, ice storms, and the like has shown over and over again that cell phone communications are simply too vulnerable to be relied upon for vital communications in emergencies. Simply put, when you most need communications, cell phones are least likely to work.

Overnight on October 24-25, 1997 Lincoln was hit be a devastating snowstorm. It was a late fall that year, and the leaves had not fallen yet. The weight of the wet snow was devastating. Huge limbs and trees were down everywhere. This photo below, taken by UNL climatologist Dr. Ken Dewey, depicts one of Lincoln's main thoroughfares, A Street at about 43rd. Tens of thousands of homes and businesses were without utilities for up to ten days. Temporary shelters were opened around town, and the police and fire departments were in full emergency mode.

I remember standing in the Emergency Operations Center on the morning of October 25th, passing out City of Lincoln portable radios to Nebraska National Guard soldiers, who were teaming up with police officers and using HumVees to locate and evacuate home-bound citizens with complex medical issues. We had the only functioning communications system in Lincoln. It kept on ticking while telephone service--both landline and cellular--was crippled across the city for days. While this was the most severe event I remember in terms of its impact on commercial communications systems, it's certainly not the only one. Our next radio system needs the same level of reliability as the one it is replacing has delivered when the chips were down.

Police officers and firefighters, are not having one-to-one conversations over the radio system. Rather, their radio traffic is one-to-many. It's a fundamental difference between a cell phone call and a public safety broadcast. Technically, you could use the same cell phone infrastructure to carry a group call, but the more serious limitations of cell phones for emergency communications lie in the design and engineering of the equipment and systems.

Ever drop your smartphone? If so, you had that sinking feeling, because we all know that the chances of it working when you pick it up are iffy. Cracked screens are a dime a dozen. How long do you think a smartphone would hold up in a foot pursuit? Do you think it would work if it got really, really wet, like directing traffic in a downpour, or on the fireground? Sure, you could encase it in the Binford 5000 case (is that reference beginning to date me?), but are you willing to bet your life on that? Public safety radios are weather-sealed, robust and mil-spec. The even greater concern, however, is not the end-user device, but rather the system itself.

Cell sites are not built to the same standard as public safety radio sites, which are engineered to withstand higher stress from such things as wind, lightning strikes, ice, and natural disasters. Public safety radio systems are designed with backups and redundancies to minimize the likelihood of failure. They also manage traffic differently, giving users priority for access to the system based on the criticality of their function. If you've ever tried using your cellphone at a big event, like a football game, festival, or mass gathering, you've probably experienced difficulty getting access to make a call. Traffic can overwhelm cell sites pretty quickly, as hundreds or thousands of users are competing for the same resources at the same time in the same area.

Experience around the country in critical incidents and events, like hurricanes, tornadoes, windstorms, ice storms, and the like has shown over and over again that cell phone communications are simply too vulnerable to be relied upon for vital communications in emergencies. Simply put, when you most need communications, cell phones are least likely to work.

Overnight on October 24-25, 1997 Lincoln was hit be a devastating snowstorm. It was a late fall that year, and the leaves had not fallen yet. The weight of the wet snow was devastating. Huge limbs and trees were down everywhere. This photo below, taken by UNL climatologist Dr. Ken Dewey, depicts one of Lincoln's main thoroughfares, A Street at about 43rd. Tens of thousands of homes and businesses were without utilities for up to ten days. Temporary shelters were opened around town, and the police and fire departments were in full emergency mode.

I remember standing in the Emergency Operations Center on the morning of October 25th, passing out City of Lincoln portable radios to Nebraska National Guard soldiers, who were teaming up with police officers and using HumVees to locate and evacuate home-bound citizens with complex medical issues. We had the only functioning communications system in Lincoln. It kept on ticking while telephone service--both landline and cellular--was crippled across the city for days. While this was the most severe event I remember in terms of its impact on commercial communications systems, it's certainly not the only one. Our next radio system needs the same level of reliability as the one it is replacing has delivered when the chips were down.

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

More than four

Last week, the committee assembled by the Mayor to make recommendations on replacement of the City's radio system and optimization of fire stations held it's first meeting. I'm chairing the committee. Last week the committee considered the need for updating the radio system, 80% of the use of which is by public safety personnel. This week, our attention will shift to fire stations.

At the same time the committee is working, the City is also conducting what has become an annual process for engaging citizens in the discussion of the City's budget priorities. This year, the online survey portion of that process is also asking about these two public safety projects. I've been reviewing the results as they are compiled, and also looking at the comments. It's apparent to me that many people are still a little fuzzy about why we think it's important to have a fire station within four minutes travel time to as many addresses in the community as possible.

Four minutes is a national standard for urban fire and rescue services, adopted by the National Fire Protection Association and widely used as the benchmark U.S. cities. The standard is worded as a percentile: travel time to life-threatening emergencies of four minutes or less, 90% of the time. In Lincoln, we are at 80% so far this year, and we've been getting a little worse as the years pass--primarily due to geographic growth.

It's important, because the amount of time from the onset of an emergency to the arrival by Lincoln Fire & Rescue equipment and personnel makes a big difference in the outcome. A few minutes delay in the event of a stroke, fire, traumatic injury, cardiac or respiratory arrest can literally be the difference between life and death. Right now, only about 89% of the addresses in Lincoln are within four minutes of a fire station. We'd like to get that up above 95%.

On the map below, you can easily see the areas most at risk for delayed response due to excessive travel time. Green is good, red is bad. The white outline represents the projected future service area of Lincoln in 2040. As you can see, the growth areas in the north, south, and east are going to be increasingly orange and red if we don't do something.

At the same time the committee is working, the City is also conducting what has become an annual process for engaging citizens in the discussion of the City's budget priorities. This year, the online survey portion of that process is also asking about these two public safety projects. I've been reviewing the results as they are compiled, and also looking at the comments. It's apparent to me that many people are still a little fuzzy about why we think it's important to have a fire station within four minutes travel time to as many addresses in the community as possible.

Four minutes is a national standard for urban fire and rescue services, adopted by the National Fire Protection Association and widely used as the benchmark U.S. cities. The standard is worded as a percentile: travel time to life-threatening emergencies of four minutes or less, 90% of the time. In Lincoln, we are at 80% so far this year, and we've been getting a little worse as the years pass--primarily due to geographic growth.

It's important, because the amount of time from the onset of an emergency to the arrival by Lincoln Fire & Rescue equipment and personnel makes a big difference in the outcome. A few minutes delay in the event of a stroke, fire, traumatic injury, cardiac or respiratory arrest can literally be the difference between life and death. Right now, only about 89% of the addresses in Lincoln are within four minutes of a fire station. We'd like to get that up above 95%.

On the map below, you can easily see the areas most at risk for delayed response due to excessive travel time. Green is good, red is bad. The white outline represents the projected future service area of Lincoln in 2040. As you can see, the growth areas in the north, south, and east are going to be increasingly orange and red if we don't do something.

Friday, October 17, 2014

Great opportunity

The Lincoln Police Department is recruiting for a Crime Analysis Manager. Since the Director's Desk is read by many analysts around the country, I am taking advantage of my blog to publicize the opening. Applications are open through November 14, on the City of Lincoln's website. Click here for the details.

Our Crime Analysis Manager, Drew Dasher, is relocating with his wife and family to Texas. He's done a great job for the past four years, and I am certain he would be happy to tell any prospects about the City, Department, and Unit.

As readers of the Director's Desk know, the Lincoln Police Department is in the front row when it comes to information resources, crime analysis, and problem-oriented policing. At all levels, our personnel make great use of our information resources, and are comfortable with information technology. Crime analysis is deeply embedded in our organization. Follow the links in the label cloud to “Crime Prevention,” "POP," or "Crime Analysis," for many examples of the type of work we do, and how crime analysis contributes to our success.

Our five-person Crime Analysis and Intelligence Unit is an integral part of most everything we do. The unit is widely respected and appreciated by our rank-and-file officers, supervisors, and the management staff. You will work with a director, chief, and management staff who understand and appreciate the value of crime analysis and the contribution it makes to our success.

The Crime Analysis Manager will join the police department's other unit managers. Currently, our Communications Center, Records Unit, Information Technology Unit, Property & Evidence Unit, Police Garage, Accounting Unit, Victim/Witness Unit, and Forensic Unit are headed by civilian managers who participate fully on the department's management team on the same footing their sworn counterparts in operational units.

The salary range for this position reflects the relatively low cost of living in Nebraska If you are on either coast, you will want to consider in particular the cost of housing in Lincoln. Take a look at home prices advertised by one of our local real estate brokers, or assessed values on the Lancaster County Assessor's website to get a sense of what your housing dollar buys in Lincoln. Transportation costs are also low. Lincoln is a bike-friendly city. My 15 minute drive from the southern edge of the City to downtown is 32 minutes in fair weather when I commute by bike, almost entirely on the paved trails network.

Lincoln is widely-regarded as a great place to raise kids. The City is unusually safe, and maintains its small-town feel despite its population of 270,000. Lincoln has great sports venues, a lively arts scene, a top-notch parks system, and the public schools are first rate. Lincoln lands on lots of "best places" lists every year.

If you are a crime analyst who is tired of a long commute to a job where you are treated like a second class citizen because you don't wear a badge, we offer an alternative. If you are expected to fetch statistics and make PowerPoints for the brass, it's not like that here. If you are looking for a chance to grow professionally, we have a challenge. If you simply want to discuss this opportunity, Drew Dasher or I would love to talk you.

Drew Dasher

402.441.7207

lpd3381@cjis.lincoln.ne.gov

Tom Casady

402.441.7237

tcasady@lincoln.ne.gov

Our Crime Analysis Manager, Drew Dasher, is relocating with his wife and family to Texas. He's done a great job for the past four years, and I am certain he would be happy to tell any prospects about the City, Department, and Unit.

As readers of the Director's Desk know, the Lincoln Police Department is in the front row when it comes to information resources, crime analysis, and problem-oriented policing. At all levels, our personnel make great use of our information resources, and are comfortable with information technology. Crime analysis is deeply embedded in our organization. Follow the links in the label cloud to “Crime Prevention,” "POP," or "Crime Analysis," for many examples of the type of work we do, and how crime analysis contributes to our success.

Our five-person Crime Analysis and Intelligence Unit is an integral part of most everything we do. The unit is widely respected and appreciated by our rank-and-file officers, supervisors, and the management staff. You will work with a director, chief, and management staff who understand and appreciate the value of crime analysis and the contribution it makes to our success.

The Crime Analysis Manager will join the police department's other unit managers. Currently, our Communications Center, Records Unit, Information Technology Unit, Property & Evidence Unit, Police Garage, Accounting Unit, Victim/Witness Unit, and Forensic Unit are headed by civilian managers who participate fully on the department's management team on the same footing their sworn counterparts in operational units.

The salary range for this position reflects the relatively low cost of living in Nebraska If you are on either coast, you will want to consider in particular the cost of housing in Lincoln. Take a look at home prices advertised by one of our local real estate brokers, or assessed values on the Lancaster County Assessor's website to get a sense of what your housing dollar buys in Lincoln. Transportation costs are also low. Lincoln is a bike-friendly city. My 15 minute drive from the southern edge of the City to downtown is 32 minutes in fair weather when I commute by bike, almost entirely on the paved trails network.

Lincoln is widely-regarded as a great place to raise kids. The City is unusually safe, and maintains its small-town feel despite its population of 270,000. Lincoln has great sports venues, a lively arts scene, a top-notch parks system, and the public schools are first rate. Lincoln lands on lots of "best places" lists every year.

If you are a crime analyst who is tired of a long commute to a job where you are treated like a second class citizen because you don't wear a badge, we offer an alternative. If you are expected to fetch statistics and make PowerPoints for the brass, it's not like that here. If you are looking for a chance to grow professionally, we have a challenge. If you simply want to discuss this opportunity, Drew Dasher or I would love to talk you.

Drew Dasher

402.441.7207

lpd3381@cjis.lincoln.ne.gov

Tom Casady

402.441.7237

tcasady@lincoln.ne.gov

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

HunchLab 2.0

A few weeks ago, we began piloting HunchLab 2.0 in Lincoln. HunchLab is a crime forecasting product from Azavea. HunchLab seeks to forecast crime by analyzing historical crime data and other information related to crime, such as weather, population density, and land use. HunchLab uses these data to predict the most likely areas for crime today, in eight hour blocks.

The output from HunchLab consists of a map of Lincoln containing a few dozen color-coded cells about the size of two square blocks. These are areas where the risk of crime is forecast to be heightened during the prediction period. These cells are approximately two blocks square. The colors represent the particular crime type for which the elevated crime risk is predicted.

HunchLab predictions are based on the analysis of Lincoln's crime data for the past five years. Where crime has occurred in the past provides a good clue as to where it will occur in the future. This is particularly true for recent crime, so crimes occurring in the immediate past are given more weight. Historical data also reveals patterns in time: crime has large peaks and valleys across the calendar and the clock.

Population density is an excellent predictor of many crime types, as is income. Densely packed low-income neighborhoods suffer more crime than sparsely populated suburban neighborhoods. Land use and zoning impacts crime. Retail businesses, such as convenience stores, restaurants, hotels and motels, grocery stores, and so forth draw people together so the chance of offenders and victims encountering one another is increased. In addition, certain kinds of businesses are related to a significantly elevated risk of crime at or around the business, such as bars and liquor outlets.

Essentially, when you gather all these kinds of data together, you can make informed predictions about where crime is most likely to occur. All of the factors that go into the prediction are based on research about the causes and correlates of crime. In fact, the commercial product emerged from research conducted at Temple and Rutgers. HunchLab goes a step further, and tests the predictions: how well did the cells identified by HunchLab’s algorithm perform in predicting where the crime actually occurred in subsequent time periods? One of the distinguishing features of HunchLab is the ongoing testing of the model, and machine learning that adjusts the predictions on the fly.

HunchLab is far better at predicting crime locations than random distribution. Although Hunchlab is predicting crime at places where most seasoned Lincoln Police Officers would recognize higher risk from their experience, there are other places that aren’t so obvious. It is also worth noting that not all Lincoln police officers are equally "seasoned."

We have helped out with the development of HunchLab 2.0 by providing data and feedback, and we are one of a handful of agencies piloting the application. For a more detailed description of HunchLab under the hood, the underpinning in criminological theory, and the research upon which it is based, go here.

Predictive analytics are getting a lot of attention in policing these days, but the same techniques can be applied to fire and EMS work. I blogged about this a few years ago, when the concept was still pretty new. Here in Lincoln, it is possible to predict fairly accurately both where we'll be sending fire engines and medic units, and when those responses will be occurring. We are using this knowledge more than ever to make informed decisions about our operations at Lincoln Fire & Rescue.

The output from HunchLab consists of a map of Lincoln containing a few dozen color-coded cells about the size of two square blocks. These are areas where the risk of crime is forecast to be heightened during the prediction period. These cells are approximately two blocks square. The colors represent the particular crime type for which the elevated crime risk is predicted.

HunchLab predictions are based on the analysis of Lincoln's crime data for the past five years. Where crime has occurred in the past provides a good clue as to where it will occur in the future. This is particularly true for recent crime, so crimes occurring in the immediate past are given more weight. Historical data also reveals patterns in time: crime has large peaks and valleys across the calendar and the clock.

Population density is an excellent predictor of many crime types, as is income. Densely packed low-income neighborhoods suffer more crime than sparsely populated suburban neighborhoods. Land use and zoning impacts crime. Retail businesses, such as convenience stores, restaurants, hotels and motels, grocery stores, and so forth draw people together so the chance of offenders and victims encountering one another is increased. In addition, certain kinds of businesses are related to a significantly elevated risk of crime at or around the business, such as bars and liquor outlets.

Essentially, when you gather all these kinds of data together, you can make informed predictions about where crime is most likely to occur. All of the factors that go into the prediction are based on research about the causes and correlates of crime. In fact, the commercial product emerged from research conducted at Temple and Rutgers. HunchLab goes a step further, and tests the predictions: how well did the cells identified by HunchLab’s algorithm perform in predicting where the crime actually occurred in subsequent time periods? One of the distinguishing features of HunchLab is the ongoing testing of the model, and machine learning that adjusts the predictions on the fly.

HunchLab is far better at predicting crime locations than random distribution. Although Hunchlab is predicting crime at places where most seasoned Lincoln Police Officers would recognize higher risk from their experience, there are other places that aren’t so obvious. It is also worth noting that not all Lincoln police officers are equally "seasoned."

We have helped out with the development of HunchLab 2.0 by providing data and feedback, and we are one of a handful of agencies piloting the application. For a more detailed description of HunchLab under the hood, the underpinning in criminological theory, and the research upon which it is based, go here.

Predictive analytics are getting a lot of attention in policing these days, but the same techniques can be applied to fire and EMS work. I blogged about this a few years ago, when the concept was still pretty new. Here in Lincoln, it is possible to predict fairly accurately both where we'll be sending fire engines and medic units, and when those responses will be occurring. We are using this knowledge more than ever to make informed decisions about our operations at Lincoln Fire & Rescue.

Friday, October 10, 2014

Collective efficacy

Marvin Krout, the director of Lincoln's Planning Department, sent the police chief and me a link to a great story from the San Francisco Chronicle, about a guy named Dan who epoxied a two-foot tall statute of Buddha to a street median in his Oakland, CA neighborhood. Dan's not Buddhist, but he spotted the statue at the local Ace Hardware, and got a wild hair.

One thing led to another, and before long, a small shrine had been erected. Offerings began appearing, a few worshipers began worshiping in the morning, tourists began visiting, Anglo, black, and Vietnamese residents were meeting each other, and crime--which had plagued the neighborhood--went down like a rock.

What this story represents is the emergence in this neighborhood of collective efficacy: social cohesion among neighbors who are willing to work together for the common good. In my forty years of public safety service, I have seen over and over how collective efficacy is the key ingredient that separates a vibrant, safe neighborhood from one that is, well, sketchy.

Collective efficacy is independent of socio-economic status. I have seen some of the poorest areas of Lincoln where the willingness of people to work together to make things better was strong. Likewise, I've seen plenty of neighborhoods where income is high and housing is good, but the residents do not even know one another--much less work collaboratively to make things better.

You can create collective efficacy where little exists. You do so in big ways and small, by meeting your neighbors, by hosting a gathering on National Night Out or the Fourth of July, getting a few folks together to cover up graffiti,organizing a neighborhood watch group, recruiting others for a Saturday clean-up at the neigbhorhood park, painting the street, sitting on the front steps rather than the back patio, planting a flower in a cracked curb, and by gluing a Buddha to a barren median strip!

It's not rocket science, and it makes a huge difference to neighborhood wellbeing, and as in Dan's Oakland neighborhood, a positive impact on crime.

One thing led to another, and before long, a small shrine had been erected. Offerings began appearing, a few worshipers began worshiping in the morning, tourists began visiting, Anglo, black, and Vietnamese residents were meeting each other, and crime--which had plagued the neighborhood--went down like a rock.

What this story represents is the emergence in this neighborhood of collective efficacy: social cohesion among neighbors who are willing to work together for the common good. In my forty years of public safety service, I have seen over and over how collective efficacy is the key ingredient that separates a vibrant, safe neighborhood from one that is, well, sketchy.

Collective efficacy is independent of socio-economic status. I have seen some of the poorest areas of Lincoln where the willingness of people to work together to make things better was strong. Likewise, I've seen plenty of neighborhoods where income is high and housing is good, but the residents do not even know one another--much less work collaboratively to make things better.

You can create collective efficacy where little exists. You do so in big ways and small, by meeting your neighbors, by hosting a gathering on National Night Out or the Fourth of July, getting a few folks together to cover up graffiti,organizing a neighborhood watch group, recruiting others for a Saturday clean-up at the neigbhorhood park, painting the street, sitting on the front steps rather than the back patio, planting a flower in a cracked curb, and by gluing a Buddha to a barren median strip!

It's not rocket science, and it makes a huge difference to neighborhood wellbeing, and as in Dan's Oakland neighborhood, a positive impact on crime.

Tuesday, October 7, 2014

While we were sleeping

Sunday morning before dawn, a pastor noticed an unfamiliar car with Wyoming plates in his church's parking lot. Thinking this odd, he called LPD. Two officers responded, and contacted a young man laying in the back seat with a suspicious story. He claimed he had come to Nebraska to visit a friend from Omaha who was supposedly in Lincoln on Saturday night. He had visited her for only one hour, and was now just napping in his car before beginning his trip back home.

In response to a question, he said that he was on probation for burglary, but that his probation officer was aware of his out of state travel. He consented to a search of the vehicle, which turned up nothing suspicious, but his explanation for his presence in Lincoln didn't make much sense. He left the lot at the officers' request. As he was leaving, one of the officers found him with a Google news search, named in a 2012 article about the arrest of a group of men for a series of over 40 burglaries in his home state.